Directed by Martin Campbell

Directed by Martin Campbell

Screenplay by Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio and John Eskow

Story by Ted Elliot & Terry Rossio and Randall Jahnson

Based on the character created by Johnston McCulley

Produced by Doug Claybourne and David Foster

Executive Producers: Walter Parkes, Lauri MacDonald, and Steven Spielberg

Starring Antonio Banderas, Anthony Hopkins, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Stuart Wilson, Matt Lescher, L.Q. Jones

Released in 1998

Being rewritten is never fun, often painful. Unfortunately, in the day-to-day business of Hollywood it is becoming more and more commonplace.

In the case of “The Mask of Zorro” I was the first of what would ultimately be nine screenwriters who worked on the movie. Only four received credit.

At first I was angry about having been rewritten so much. But as the years have passed, I now see it as amusingly appropriate. This stems from the fact that the Zorro franchise itself is a series of appropriations, revisions, and embroidered facts.I feel fortunate that I was one of them, especially after the basic story I laid out in my first draft – the Old Zorro mentoring a Young Zorro (the brother of bandit Joaquin Murieta) to take his place and exact revenge and retrieve his daughter – weathered more than 25 revisions.

There is no doubt in my mind that Johnston McCulley, who created the Zorro character in “The Curse of Capistrano,” a pulp magazine serial published in 1919, was inspired by the California Gold Rush bandit Joaquin Murieta. McCulley was a former-newspaper reporter-turned-author and amateur historian. He would have been well aware of the Joaquin saga, even with the most cursory research.

In his book Anybody’s Gold historian Joseph Henry Jackson questions whether Joaquin ever existed at all. And if he had, was he an individual or a composite of several Latino outlaws operating in the Mother Lode in the early 1850s.

One contemporary account says he was originally from Chile. Others state he was Mexican. Spanish was added later. And of course he could have been a native Californio, too.

What is known is that for the first three months of 1853 a criminal answering to the name of Joaquin terrorized the California Gold Rush country. He and his band were responsible for at least 24 murders – mostly defenseless Chinese placer miners – before Captain Harry Love and his California Rangers claimed to have ambushed and killed the outlaws. As proof, Love “lectured” throughout the state with the severed head of a Latino male preserved in a large glass jar. In those days before forensics, the veracity of Love’s claim could not be determined. (The head was lost in the San Francisco earthquake-fire of 1906.)

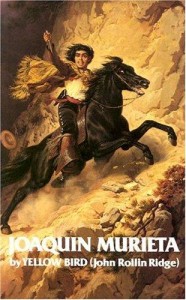

Little more than a year later in 1854 the scant facts about Joaquin were collected, embellished, and sensationalized in a 90-page book titled The Life and Times of Joaquin Murieta, the Celebrated California Banditwritten by Yellow Bird.

Yellow Bird was the Indian name of a young San Francisco journalist, John Rollin Ridge, himself a somewhat-fabricated identity. Ridge was a half-blooded Cherokee Indian whose tribal elder father was involved in the signing of the agreement that led to the removal of the Cherokee from their native Georgia to the Indian Territory of Oklahoma via the infamous Trail of Tears. Later, his father was murdered by an enemy tribal faction. Ridge vowed revenge and killed one of his father’s assassins before fleeing to California in 1850.

After failing as a miner, he drifted to San Francisco where he began writing for newspapers. Shortly thereafter he heard the story of Joaquin and began work on the book that would romanticize the outlaw into a Robin Hood-like character. Perhaps in the Joaquin story he saw a way to express the injustice he had experienced in his own life.

Ridge’s slim volume would spawn a generation of Joaquin stories. There would be dime novels, serials, plays, “authentic” histories, each one by a different author, each one pirating the facts and perpetuating the myth.

On the heels of this came Johnston McCulley who, I’m sure, took the folkloric image of the wild-eyed, stallion-mounted Joaquin, gave him a mask, a cape, and some manners to create the swashbuckling Zorro.

When I came aboard to write the screenplay, I wanted to compose a story that would unite the modern hero with his 19th-century roots. Little did I know that my contribution to the franchise would get trundled over by so many.

But I can’t complain. In this case getting rewritten is not an injustice – it’s a tradition.